Historical Background

Nitshill and the Levern Valley

In 1882-4, Frances Groome's Ordnance Gazetteer of Scotland described Nitshill as:

Nitshill, a village in the SE corner of Abbey-Paisley parish, Renfrewshire, near the right bank of Levern Water, with a station on the Glasgow, Barrhead, and Kilmarnock Joint railway, 2 miles NE of Barrhead, and 4 ¾ WSW of Glasgow. It has a Free church, a Roman Catholic school, and chemical works (1807); and it is largely inhabited by workers in neighbouring coal-mines and quarries. Population (1841) 821; (1861) 1029; (1871) 986; (1881) 1001.’

It is unclear how Nitshill got its name, but legend has it that the village was originally named Nuttishill, due to it being a small hill topped with hazelnut groves. This is supported by a reference documented in the poll tax rolls of the Paisley Abbey Parish records, which states that, in 1695, a Mr Robert Miller of Nuttishill had to pay a tax of 1.17s.2d. to King William III. Anecdotal evidence suggests that people, now long gone, used to pick the hazelnuts from that same wood, until both it and the hill were levelled by bulldozers in the 1920s. During later excavation work to prepare the ground for the foundations of Bellarmine School, engineers discovered an old silted bed of the Brock Burn that contained dozens of ancient hazel-nuts.

Archival evidence relating to Nitshill is scarce and what is available focuses mostly on Crookston Castle and the Barony of Darnley. However, research has brought to light a few snippets of information about the people from the Levern villages, which includes Nitshill and nearby Hurlet. For example, this wider area has a military past and, in 1138AD, a large body of soldiers, given the group name of ‘Levernani’ were recruited from the lower Levern villages. Records suggest that the Levernani were formidable fighters under the leadership of Walter Fitzalan, the founder of Paisley Abbey, but they experienced great losses at the Battle of the Standard, near York. The battle, also known as the Battle of Northallerton, was an attempt by King David I of Scotland to exploit the dynastic power struggle in England between Stephen and Matilda, the latter being David’s niece, though he was also related to Stephen’s wife. Seeking to reclaim some land and to capture additional territory, David invaded northern England in the summer of 1138, but he was fought and defeated by an army raised by the Archbishop of York.

Battle of the Standard, 22nd August 1138, by Sir John Gilbert

The Levernani lost many men but survived as a unit and years later, in 1164, it played a major part in a battle at Renfrew against Somerled, the Lord of the Isles. Somerled was a military and political leader of the Scottish Isles in the 12th century. He was known in Gaelic as ‘ri Innse Gall’: ‘King of the Hebrides’. Following the deaths, in 1153, of David I of Scotland and King Olaf of The Isle of Man, Somerled took his chance and made offensive moves against both Scotland and Man and the Isles. Somerled eventually manoeuvred his way to extending his kingdom from the Isle of Man to the Butt of Lewis. This brought both Vikings and Scots under a single lord and they came to share a single culture to become a powerful race known as the Gall-Gaidheal, literally meaning 'Foreign-Gaels'. However, Somerled eventually overreached himself when he tried to further extend his powers and came up against the Stuarts, who had made inroads into the west coast. Somerled assembled a sizeable army to repel them and marched into the Stuart’s territory of Renfrew, which was defended by the Levernani, amongst others. It is unclear exactly what happened there but, at the end of the day, Somerled and his son were both dead and his army retreated from the area. After this engagement, the Levernani seem to have disappeared from history.

Another item of historical note took place in 1180, when a hospital for sick brethren was founded by Robert de Croc, the builder of Crookston Castle and a church at Neilston, all built on his lands. This is thought to have been one of the earliest formal hospitals in Scottish history. Named after Sir Richard Croc, Laird of Cowglen, and one of the oldest castles in the West of Scotland, Crookston Castle is reportedly the last medieval castle in Glasgow. Built on top of a hill, the castle is actually a combination of two castles, with one sitting inside the other, and is surrounded by a ring-shaped ditch. The ditch and the original castle, which contained a chapel, were built by Sir Richard in the twelfth century. By the 14th century, Sir Richard’s descendants had lost their lands when most of the Levern valley was acquired by a branch of the Stewart family. Sir John Stewart extended the original castle structure after he inherited the lands of Darnley in 1404.

The newer castle had four corner towers and is estimated to have been over sixty feet high and covered a ground area of sixty feet by forty feet. It had a storage cellar, well, kitchen and sleeping quarters on the ground floor, a Great Hall on the first floor, and private stairways and apartments at the east side of the building. At the bottom of the north-east tower was a pit-dungeon. The exterior of the castle was limewashed and the main entrance was barred by a forehouse, heavy doors and a portcullis. All of these features were designed to keep out small armies of lightly-armed men whilst also providing comfortable habitation for the Stewart family and their retainers.

Famous on French battlefields during the One Hundred Years War, Sir John’s troops became the mighty Scots Guards - the personal bodyguard of the King of France. In 1429, Sir John was killed in an ambush while trying to steal some salted herrings from the enemy to feed his men.

A descendent of Sir John, Henry Stewart, later became the Lord Darnley who married Mary, Queen of Scots in the 16th century. It is said that Lord Darnley and his wife often sat beneath a sycamore tree when they visited Crookston Castle. Today, that sycamore tree, known as a ‘plane tree’ in Scotland, stands at the corner of Nitshill Road and Kennishead Road and is a protected heritage site surround by a wrought iron fence.

Eventually, Crookston Castle succumbed to the elements.

Eventually, Crookston Castle succumbed to the elements, was abandoned, and fell to ruin. However, it has not been forgotten and both it and the land that surrounds it is now a popular beauty spot and a venue for educational visits and storytelling. The documented history of Nitshill and nearby Hurlet gathered pace during the seventeenth century against a background of mineral extraction (see: Mineral Extraction). It was not long before pioneering industrialists began to invest heavily in machinery and infrastructure to exploit those seams and the land above them.

Nearby fields were used for bleaching cloth, which was an important process in wool, cotton and linen production, and was often in preparation for dyeing. Before the introduction of chemicals, bleaching was a process whereby cloth was treated with stale urine and then laid out in fields to be dried by the sun. Bleachfields were simple areas where cloth was laid out in the sun to bleach. The bleaching process was later shortened by replacing urine with sour milk, and shortened again by replacing milk with sulfuric acid. In the latter half of the eighteenth century, bleachers started to use lime in the bleaching process, but this was a dangerous process. In 1788, Charles Tennant bought bleaching fields at Darnley and experimented with alternative ways to shorten the bleaching time. Tennant came up with the idea of using a combination of chlorine and lime to produce the best bleaching results. After several failed attempts, Tennant finally came up with a successful method that proved to be effective, inexpensive, and harmless. He was granted patent no. 2209 on 23 January 1798 and continued his research to develop a bleaching powder (patented no.2312 on 30 April 1799). Tennant had formed a partnership with four friends in 1974; his partners were: Dr William Couper, the legal advisor to the partnership; Alexander Dunlop, partnership accountant to the group; James Knox, who managed the sales department; Charles Macintosh, an excellent chemist, was the fourth partner and he also assisted in the invention of bleaching powder. Macintosh had also established an Alum Works on the banks of Lavern Water in what is now Househill, and he was the inventor of the well-known waterproofing process used in raincoat manufacture (the variant spelling of Mackintosh is now standard). Following the granting of the bleaching powder patent, the partners bought land beside the Monkland Canal in an area known as St. Rollox, just north of Glasgow, and built a factory that produced bleaching liquor and powder. St.Rollox land was cheap, was close to a good supply of lime, and the nearby canal provided excellent transportation. Before long, production was moved from the Darnley bleachfields to the new factory, but the bleachfields remained in use.

By 1790, Nitshill and Hurlet had become a prosperous industrial hub. Sadly, such industrial growth was not without consequences, as exemplified by the Victoria Pit disaster in 1851, in which 63 men and boys were killed. (See: Coal Mining & the Victoria Pit Disaster).

Nitshill also had a chemical works and several quarries but was mostly recognised as a coal mining village throughout much of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and its legacy of great bings of waste fed the Nitshill Brick Works for many years. Like many coalmining villages, Nitshill was surrounded by lush green fields and farmland, but it only took a short walk to reach areas where miners laboured far underground, lime and fire clay workers toiled, and folk earned a living in any way they could. Nitshill railway station was opened by the Glasgow, Barrhead and Neilston Direct Railway on 27 September 1848. It was later used by the village’s mill girls to travel to Neilston, where they worked 12-hour shifts from 6am to 6pm. Although work for Nitshill’s workers was fairly plentiful and regular at that time, wages were very low. Nonetheless, Nitshill, with its half a dozen pubs and a few shops clustered around the main street, was the hub of that industrial enterprise.

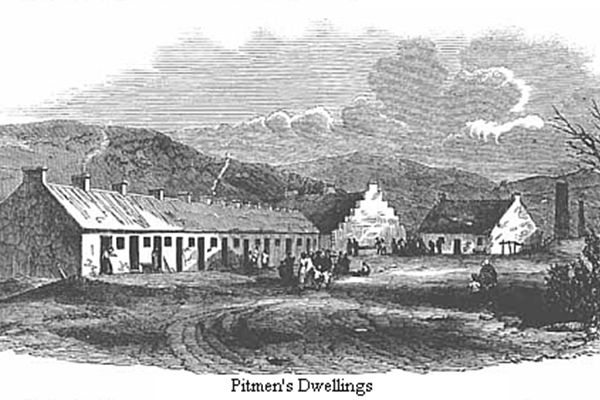

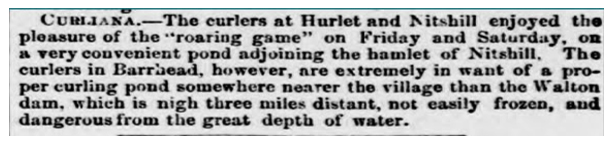

'Nitshill Pond'

Winter curling was a popular pastime and local newspapers reported curling match scores, including those of a game played on 'Nitshill Pond' on February 7, 1847. It was won by John Binnie over ten other competitors, with a score of 7 points. Nitshill’s curling pond was the envy of its neighbours, as might be observed from this comment in the Paisley Herald and Renfrewshire Advertiser, Saturday 9th January 1864:

Local historian, JB Hunter, wrote about what life was like around the turn of the century:

Anyone born in the age of steam and horse transport as I was, must have memories from schooldays of the changing ways in the world just ready to erupt into another age of surprise and progress, and this was especially so in our village life in ‘Nitshill.’ In the 1890s lighting was by paraffin lamps and by gas in a few places. Dry closets and open ashpits were all over the place. Travelling from the village was only by train or walking. Ruling officialdom seemed to be a bit afraid of new methods because when a road roller or thrashing mill went through the place, they were led by a man carrying a red flag in case they would exceed five miles an hour. But we boys saw the changes coming when Watty Crebar came shopping in his newly built horseless car, and his son George began experimenting with gliders before we had heard of the Wright Brothers or Bleriot. Around 1870, the Darnley hospital was opened to replace the timber structure in Barrhead Road, opposite Pollok golf course now used as a riding school. A little later, I think in 1909 I remember going to the polling station at election time just out of boy’s curiosity. My pal that evening wore red white and blue as his father was a well-known Liberal. The change from that time is that my schoolmate is now a well-known Labour M.P. Seeing a few volunteers off to the Boer War was an event, as nearly everyone was at the railway station to bid them farewell. About this time, it was interesting to hear from someone who remembered the Nitshill Pit disaster in 1851 when 63 men lost their lives, and again from one who had actually paid tolls at Darnley to old roadman Reilly, who collected the tolls.’

Mr Hunter was a football fan and recalled that:

Football was the popular sport, and it was here the original ‘Hi-Hi’ man, Jock Taylor, was heard on Saturday evenings when he arrived home after watching the old 3rd L.V.R’s. The villagers got their first look at Rangers when they played a friendly against Levern Victoria on Holm Park and now Newfield Square. Football players home from England during the closed season, enjoying their £208 a year, were an attraction for the boys, and none more so than Jock McMahon, wearing his cup medal won by Manchester, prior to the whole outfit being suspended Sine Die by the E.F.A. for paying more than allowed by rule. The local football pitch went back to agriculture about 1905 and anywhere a ball could be kicked was utilized until the Royal Vics started up at Darnley in 1910, and until the great war began, their record was: Renfrewshire Cup – won twice; Paisley and district cup – won twice; R.U. once: Barrhead and district league – won once; Scott Cup – won once; Pollok Tourney Final and Scottish Cup – last eight out of 269 entries. The man behind the Royals was dynamic Jas. F. Montgomerie, now Capt. Montgomerie M.C. O.B.E. Another outfit was Levern Thistle who played at the Hurlet, and who brought out a few senior players, amongst whom was Bobby Templeton who played for Hibs and finished as manager before the McCartney days. Templeton learned his boyish football where the bowling green is now and lives where ‘Sam’s’ shop is at present.’

Although its workers were poorly paid for their labour, they were intent on improving their lot and, during the early 1900s, Nitshill villagers petitioned for a public hall. The building was financially assisted by Miss Dove of the cottages in Glenlora, who later became Lady Congleton in Cheshire.

Househill Mansion

One of the most famous properties in Nitshill was Househill Mansion, which was built in the early 19th century to replace an earlier house on the lands of Househill belonging to the Dunlop family. In 1477, the lands of Househill were owned by Sir Thomas Stewart of Minto, who was the Provost of Glasgow in 1472. The estate was sold to Thomas Dunlop in 1646 and was retained by his family until 1719, when Thomas' grandson sold the estate to John Blackburn, a merchant who traded with Britain's then American colonies. In 1750, Blackburn's son Andrew sold Househill to Robert Dunlop, another merchant, whose brother was Provost Colin Dunlop of Carmyle. The estate, which now included the grand Househill Mansion, was later home to John Cochrane and his wife Catherine Cranston, proprietor of Miss Cranston's Tearooms, including the Willow Tearooms in Glasgow that was designed by Charles Rennie Mackintosh. In 1904 Mrs Cranston commissioned Mackintosh to redesign the interior of her Househill Mansion and its furniture. Catherine Cranston was widowed in 1920 and sold the house. It was later badly damaged by fire and demolished in 1930.

The author, C.R.W. later wrote about ‘Old Nitshill’; the following is an extract from his notes:

The people of old Nitshill seem to have called themselves variously Nitshillonians and Nitshillites. Which of these is best is hard to say but as in all villages the older citizens talk affectionately of notable friends who have gone…one of these being Jim Currie, the Gasman, who lived in his cottage next to the gasworks on the west bank of the Levern where it flowed under the Nitshill-Hurlet Road. Mr Currie although he had lived for more than ninety years in the village was an in-comer having been born elsewhere. He had been for many years the manager of the two-man gasworks which drew its coal from the Waterloo and Watermally Pits at Hurlet. The two men worked about the retorts and the gasholder which was a well-known part of the industrial landscape. Jim and his assistant knew every nook and cranny of the village for every house was regularly visited in the course of their duty. It was Mr Currie who emptied the pennies out of the gas meters into his Gladstone bag for transfer to the two-wheeled money-box outside.

Old Jim died at the ripe old age of one hundred and two. Many were the tales he had to tell of his long association with Nitshill. He remembered the Old Toll Bar at Darnley, where the road tolls were collected. He had helped as a lad at the milling of grain at the Darnley Mill Farm. He had watched the prowess of Sergeant Middleton, the local crack shot rifleman at the Darnley Firing Ranges, behind Darnley Mains Farm. He had seen the building of Darnley Hospital in the eighties and of the Fire station later. He told of the limestone quarries that belonged to the Kirkwood family who lived in the historic Darnley House until it was pulled down. This house and Queen Mary’s Tree opposite Darnley Mill Farm are traditionally associated with the wooing of the young Queen by Lord Darnley.

He told also of how the Misses Cranston of Househill were driven daily in their coach-and-pair to Nitshill Station on their way to their restaurant in Glasgow. Mr Donohue their coachman-gardener also had the pleasure of delivering flowers and plants from their beautiful gardens to the restaurant for the delectation of their customers. He related the pranks of the boys about Howdens Lawn and the Tap-o-the-Knowes, round the pitheads and on the railway tracks that criss-crossed the district. He told of the drowning of two children in the lade. This was a small canal which left the Levern near the Levern Church and carried water at a higher level than the falling river. This water was used to supply the Dam, which was used as a curling pond, and to drive the mill-wheel in the alum works whose site is now occupied by the English Electric Company. Thereafter it re-joined the river on its way to meet the White Cart.

On his hundredth birthday, 15th October 1960 Jim was the proud recipient of the Queen’s congratulations. To his relatives and friends who gathered in his cottage to be with him on that day, he was reported by the Barrhead News to have asked what all the fuss was about.

Nitshill was part of Renfrewshire until 1926, when it was incorporated into the City of Glasgow. The change in local government was mainly related to education and community services such as roads, water, sewerage, and housing. At the end of WWI, the village consisted of just a few streets. It grew on a small scale with the addition of cottage flats built prior to World War II; after which it was substantially expanded to accommodate people relocated during the Glasgow slum clearances in the 1950s and 1960s.