Nitshill’s Community since WWII

Nitshill has changed much over the twentieth century. The extraction industries disappeared long ago, as did brick manufacturing in the 1970s, and social life also changed. A century ago, there was a football ground not far from the station, and villagers regularly watched or participated in events such as wrestling, boxing, dog racing, tennis, golf, and clay pigeon shooting within the village boundaries. The village housed at least five pubs, including the Volunteer Arms, the Railway Inn and the Royal Oak, and there was also a pub called the Nitshill Inn. The Railway Inn organised miniature bowling for the locals, which was said to be very popular with miners during the pre-WWI miners’ strikes.

Nitshill fell within the county of Renfrewshire until about the 1920s, when it was incorporated into the City of Glasgow for reasons related to education and community services such as roads, water, sewerage, and housing. From then on, Nitshill grew from being just a few streets, to include cottage flats during the interwar period, followed by substantial expansion to accommodate people relocated during the Glasgow slum clearances in the 1950s and 1960s.

The Hurlet junction, 1905. Some of the houses on the left are still there today. In the 1950s there was a garage and petrol station where the field is in the background – looking towards Paisley.

Photograph by Robert McGlone

1920s-built cottage flats on Nitshill Road

As with other postwar housing developments across Scotland’s central belt, this expansion was not entirely successful and Nitshill experienced multiple socio-economic issues that lead to some notoriety. However, there have since been moves towards improving the district with the demolition or regeneration of much of the postwar housing and schools and towards increasing awareness of Nitshill heritage, which includes a focus on the village’s monuments and memorial stones to miners and war heroes.

Around the end of WWII, two hugely influential studies explored Glasgow’s mass overpopulation and slum housing problems and attempted to provide robust solutions. The Bruce Report, published in March 1945, led to an intensive programme of regeneration and rebuilding efforts which took place in the city and its surroundings between the mid-1950s and the late 1970s. However, in 1949, an alternative plan was put forward by a team led by Sir Patrick Abercrombie and Robert H Matthew. This Clyde Valley Regeneration Plan recommended an overspill policy for Glasgow and the rehousing of much of the existing population in new towns outside the city. Glasgow at that time had a population of around 1,130,000, and the authors suggested the rehoming of 550,000 Glaswegians into New Towns at East Kilbride, Cumbernauld, Bishopton and Houston. The Bruce report preferred rebuilding and rehousing within the city boundary. In the event, much of the slum clearance involved the relocation of people to outer Glasgow rather than outside the city. The building of high-rise flats was planned for the inner zone, whilst the outer zone would involve the creation of new housing estates at Castlemilk, Garscadden, Nitshill and Priesthill, and part of Pollok. Town planners have stated that the ensuing friction and debate between the supporters and spheres of influence for these two rival reports led to a series of initiatives designed to transform the city over the following 50 years.

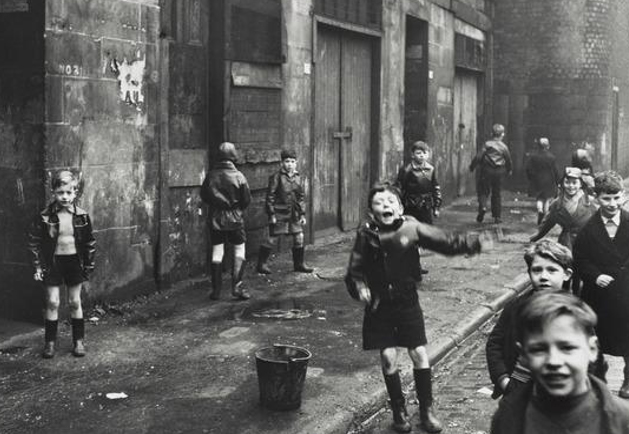

Courtesy of Elaine Duerden, ‘The Gorbals, 1950s’.

Perhaps inevitably, many of the old buildings in Nitshill were demolished as the village grew to accommodate those people relocated from Glasgow during the 1950s and 1960s, many of whom came from the Gorbals area. An unintended consequence was that the slum clearance programme severely disrupted networks of old communities and extended families. Nitshill’s new schemes had few shops and businesses, and no cinemas or leisure facilities. JB Hunter noted that:

After the WWII, the new building schemes went ahead, and the last signs of a village community floated into the past. We lost the old names like Wellington Road, Waterloo, Turnberry Road, Victoria Road, Paisley Road, Thornlie Road, etc. When I was first able to count, I managed to tally five pubs and one licenced grocer, from Levern School to the railway bridge, for around 1,000 of a population. Today I count the same number for 30/40,000.'

New residents often lived far away from their places of work and there were few opportunities for work locally. Worse yet, the post-war tenements were of poor quality and suffered from damp, condensation, lack of soundproofing, and budgetary cuts imposed by central government resulted in Glasgow Corporation, later Glasgow District Council, being unable to adequately maintain the properties at even basic levels. Across Glasgow during the past forty years, many surviving local industries and manufacturing jobs were threatened and then lost amidst the clamour for housing land, with many jobs being gradually outsourced to overseas countries. Unemployment in and around Nitshill rose expeditiously during the late twentieth century. Crime was an issue. It has been said that “those who could, left the area”. In general terms, the remaining population often endured poverty, ill-health, and lower life expectancy, though it must be stressed that this description would not apply to everyone in Nitshill, nor to those people living in the surrounding conurbations. Indeed, many people have only good memories of those times.

There has been a sustained effort to improve Nitshill and the wider area in recent years, and many of those post-war schemes have been demolished and replaced with newer housing stock. The same thing happened elsewhere, with many of the post-war housing schemes in Greater Pollok, Red Road and Easterhouse having now been demolished. Nitshill is now predominately a housing area and only one pub remains, though there is still a variety of shops. Three new school have been built in recent years and there are open spaces for people of all ages to enjoy. Nitshill is changing once more.